A NIGERIAN SOUL IN GLOBAL MOTION. A LIFE IN TRANSLATION: DREAMS, PRESSURE, AND BECOMING.

Photography Danilo Falà

Art direction Federica Trotta Mureau

Text Niccolò Lapo Latini

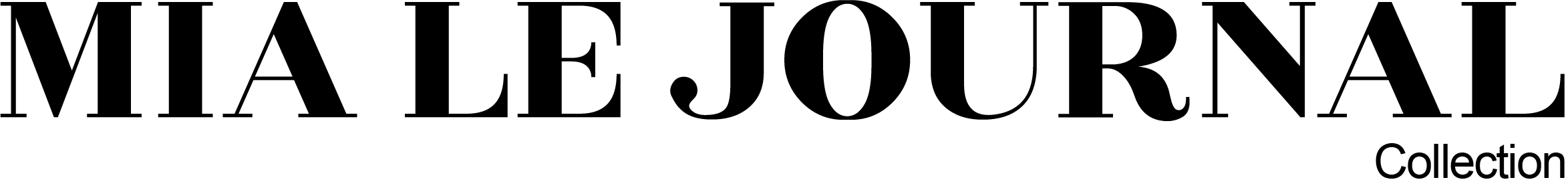

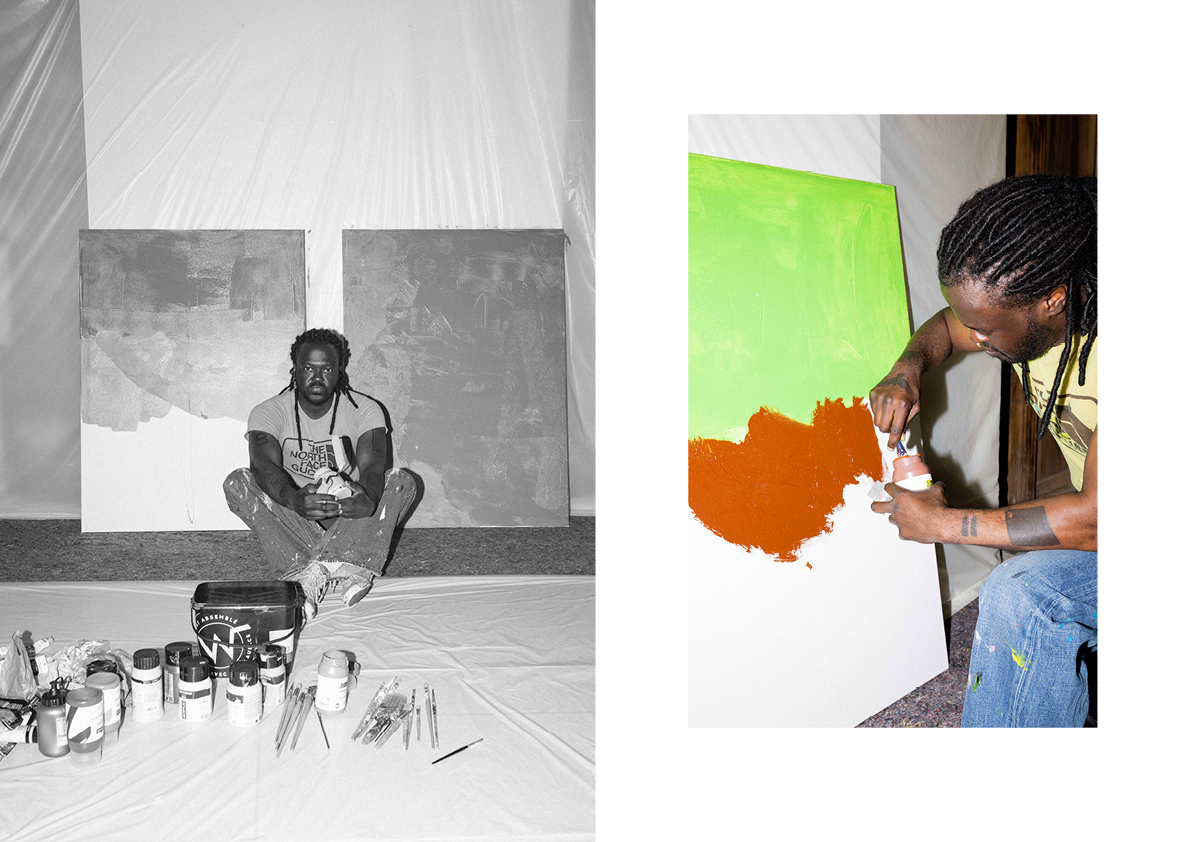

ADÉBAYO BOLAJI, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, 19th June 2025 // In the quiet depths of southern France, far from the n oise of the world, embraced like a child by the loving hospitality of Château des Alpilles, a moment of stillness unfolds — a time for absence, self-reclamation, and peace // Restoring his beloved paintings and envisioning the next leap in his artistic journey, Bolaji builds on the success of his recent residency in Jaipur. The works created and preserved at Sattva Theatre & Art have now found a home in one of India’s most prestigious galleries — Nature Morte. This summer, Bolaji presents his solo exhibition “What The Flame Could Never Burn” in Mumbai.

The wandering spirit of Adé is on an eternal quest — for his destiny, for a new home, for a dimension where both h is future and his art can truly belong. His life has been wholly devoted to experimenting with the purest forms of expression — not only to connect with an audience, but to mirror himself with honesty and depth. From a past marked by hardship and abandonment, through the crowds and the confusion of identity, he has journeyed toward revelation. Through cinema and acting, into writing and sculpture, and ultimately finding the clearest seal of his creativity in painting, Adébayo Bolaji has discovered a new dimension from which to begin again. Forever in search of answers to life’s deeper questions, his practice is not merely artistic — it is spiritual, visceral, and profoundly human. An artist who doesn’t just create, but listens, transforms, and transcends.

Adébayo Bolaji.

You started acting as a teenager and later appeared in major films like Skyfall and Les Misérables. What does painting represent for you compared to performing arts? Does it have to do with the idea of “not pretending”—a space where, unlike film, you can project only the essence of Adébayo onto the canvas, without needing to corrupt or dilute it to align with the vision of third-party directors outside of your mind and life?

Absolutely. Painting, for me, is a space of direct resonance — it’s where I’m not stepping into someone else’s vision or translating myself through a character or a script. It’s about letting something deeper move through me and materialise on the canvas. And by resonance, I mean the effect when something — a sound, an idea, a feeling — connects deeply and continues to affect you, shaping your thoughts or emotions beyond the initial moment. In acting, there’s the thrill and discipline of inhabiting — of being in line with a director’s world and shaping yourself to fit that. But painting is the opposite: it’s about disappearance — not in the sense of hiding, but in the sense of stepping aside to let presence take over. Lately, I’ve been exploring this idea in my writing — I call it the Line. It’s the creative guide or relationship, where you stop the frantic searching and allow yourself to simply be — within space, within moment. When I paint, I’m not pretending. I’m not lying. I’m not performing. I’m entering a space, hopefully, where essence, presence, pattern, and even silence can speak. I’ll use those words a lot, by the way, as they’re themes I’m currently dealing with — words like presence, which can be the state of being fully here: attentive, open, and engaged — where your mind, body, and spirit are in harmony with the moment, without distraction or fragmentation. It’s not even about “projecting Adébayo” onto the canvas — it’s more like letting go of the need to define myself at all, and instead working with whatever resonates in the moment. I listen to the resonance between me, the materials, the idea — and that’s what shapes the work. It’s smarter than we think, if we give it space.

Your work showcases a rich and powerful use of color. How do you choose your color palettes in your paintings, and what do these colors represent to you in relation to the themes you explore? Have you ever felt a connection to the images and icons of North African painting? Is it something you consciously draw from in your work? Growing up in a large Nigerian household in West London, has Nigeria evolved and become embedded in your art, or does it still reside in your heart?

For me, color isn’t just a visual choice — it’s a resonant field. By resonant field, I mean the invisible atmosphere that color creates — the way colors vibrate, interact, and amplify one another across a surface, shaping not just how we see, but how we feel. It’s the emotional and energetic space a color palette opens up, where each hue doesn’t just sit alone but affects — and is affected by — the others, creating a living, felt presence on the canvas. I work instinctively, listening for what a painting is asking for — where it wants to pull or vibrate. Because it’s visceral for me — it always has been… very intense, actually. Color becomes a way of creating space, of opening up areas within the canvas that hold emotional or spiritual weight. I’m drawn to deep contrasts — color as tension, as softness, as pause. I’m aware that people sometimes sense echoes of North African sensibilities because of the symbols I use, and Yoruba sensibilities or broader African visual rhythms in my work — but I don’t approach it consciously. It’s more like these patterns and sensibilities live in the residue of who I am. At least I think so, for now… memory, geography, ancestry — something like that. Growing up in a large Nigerian household in West London, Nigeria isn’t something I need to force into the work — it’s already there. It lives in my palette, my rhythms, even my silences. But it’s not static; it’s evolved, just as I’ve evolved. And I’m grateful for that. The Nigeria in my art is not a nostalgic flag or fixed identity — it’s a living pulse — and I’m not sure one can teach that, per se. Ultimately, my palette is shaped by continued lived experiences.

Adébayo Bolaji.

Some of your paintings seem to carry spiritual or religious references. Is religion something that plays a role in your art, or is it more about a broader exploration of identity and culture? If you’d like to share, how has your understanding of faith evolved through your life experiences and encounters with different people?

For me, I wouldn’t separate spirituality from identity, culture, or even creative practice — they’re all part of the same pattern, space, world — or at least, can be. I grew up within the Christian faith, and it shaped my early language for understanding meaning, presence, and surrender (a challenging concept). I see faith less as dogma or inherited ritual, and more as an ongoing relationship — that’s key. Christ, I find fascinating because — take artificial intelligence, for example. The reason AI works so effectively is because it draws on preexisting patterns within humanity: common needs, shared desires, recognizable goals. AI’s “knowing” comes from learning those predictable human rhythms. Now, when I think about Christ — who He said He was, who He is — what strikes me is how His presence completely disrupted human expectation. People expected certain things from a king, from a leader, from someone claiming divine authority. But what confounded them was precisely what wasn’t predictable: a love so radical, so self-emptying, it looked to them like irresponsibility, even self-destruction. From the Christian faith perspective, of course, it wasn’t destruction — it was the ultimate act of love. But it’s that unpredictable, unsettling nature of love — a love that breaks pattern — that I find both fascinating and, honestly, a little bit terrifying. In my art, I’m interested in that space — the space where something greater meets the material world. The canvas becomes a site where I practice being attentive, where I listen for what wants to appear rather than impose my will. So yes, you could say my work carries spiritual references, but not in a doctrinal way. It’s not about illustrating religious icons or stories — it’s about exploring the line between the visible and invisible, the human and the sacred, the known and the felt. My faith, if I can put it simply, has evolved into a practice of attentiveness and trust — trusting the process, the mystery, and the moments of harmony that come when you stop forcing and start listening.

You’ve mentioned trying your hand at law, graduating with great difficulty and psychological strain, before transitioning into the arts. What are your thoughts on the academic system and the idea of artists and actors often not completing their university studies? Do you think it’s due to a lack of interest, a flaw within the educational system, or more about finding a deeper calling outside traditional academia?

I don’t think it’s simply a matter of lack of interest or even a failing in the academic system — it’s more about realising that we’re not all built the same. When I look back at my time studying law, what weighed on me wasn’t the difficulty of the material — it was the psychic pressure of knowing I was out of harmony with where I was meant to be. Harmony is something we all feel, and most of the time can’t articulate. We know instinctively that something is just not right, yet struggle to find the right tools or support to comprehend and manage it. Artists, actors, creative people — we often have to follow a different line through the world, one that doesn’t always run smoothly within structured systems. It’s not better or less than — it’s just… different. Academia is built on measurable outcomes, fixed curriculums, intellectual rigour — all of which are valuable. But creativity, for me, often lives or begins in a space of coherence in feeling, yet without a common language (at least in the beginning). That’s why I keep using words like resonance, intuition, listening — all of which have an inherent intelligence. It often doesn’t fully unfold in systems designed for logic and linearity. It makes intellectual sense later — just not necessarily at the start of its process. You have to be brave enough to stick around and be patient with it. That said, I have great respect for education, and I don’t romanticise the idea of abandoning it. But I do think there’s a conflict for many artists when they feel their deeper calling pulling them outside the formal structures — not because they’re lazy or disinterested, but because they’re seeking something the system isn’t designed to provide. I think some people who are neurologically different feel this way too. In my own journey, the psychological strain came from trying to live in a way that didn’t match the deeper rhythm of who I am. Once I surrendered to the art, to the theatre, to the painting — things began to align. Not easily, but truly.

Can you share some experiences from your childhood that have shaped the themes in your work? How heavy is the burden of living up to the desires and aspirations that parents—consciously or unconsciously—impose on their children, setting goals and expectations that may not align with their true spirit, characteristics, or will?

Growing up in a Nigerian household, there’s a deep cultural inheritance of aspiration, survival (especially when my parents migrated to London), and expectation. Parents, often out of love and sacrifice, project dreams onto their children — dreams shaped by what they believe will secure safety, success, and dignity. I felt that intensely. That’s how the law degree happened — a forced idea from them. The burden of wanting to make them proud, of wanting to live up to the sacrifices they made, even when it didn’t fully make sense with who I was becoming. Despite that burden, I’ve been shaped by profound wisdom and love. Nigerians, generally speaking, know how to hold space. We are dreamers in that we believe words hold power, and this means that there is the idea of being able to shape your space and not be a victim of it. So you can find a Nigerian in a desperate position, yet that individual will change the narrative in their head. Since we know stories hold power, we are careful about the stories we tell ourselves — to hold space to exist and to keep going. I love us. Here is one experience: the wisdom of my mother choosing not to burden a child with adult drama that could lead to a troubling mindset. My mother waited until I was of age — when I could handle nuanced situations — so as not to label people as simply good or bad. That’s beautiful emotional intelligence right there.

Adébayo Bolaji.

“We Are Elastic Ideas” offers a minimalist, philosophical exploration of life’s mundanity. How did your background in performance and visual art influence the poetic form and the themes you explored in this book? In your poem Dichotomies, you delve into contrasts and dualities. How does this theme manifest in your visual art as well?

I actually think poetry has always been present in my life — even before I was conscious of it. As a child, I often thought abstractly: I’d begin with feeling first, and only later search for the words to clothe that feeling. For me, poetry is about taking the language we use every day and reassembling it — to convey an inner world, a private emotional or contemplative space made manifest through words. That’s why, when someone reads a poem, they feel seen: it’s the unseen brought into form. In a sense, poetry grounds the unseen with the seen — it binds what we feel with what we can touch. And I think that same impulse runs through my visual art and performance work. Theatre has its own kind of poetry, shaped by narrative, by pulse, by the measured unfolding of time. You experience theatre within a defined space and duration — it holds you inside a moment. Visual art, by contrast, offers more open-ended time: whether figurative or abstract, it’s about making the unseen visible, but the viewer decides how long to stay, how deep to go. So in many ways, poetry, painting, and theatre weave through each other in my practice. But if I had to say which grounds the others, I’d point to theatre — because performance is act, it’s measured real time, where the moment is held collectively between artist and audience. I say grounds in the sense that its lessons grounded me. As for Dichotomies and my fascination with contrast, I think I’m always working inside the push and pull of opposites — dark and light, seen and unseen, silence and sound. You can’t fully know one without the other. In my paintings, I let contrasts clash: colour against colour, line against figure, expectation turned on its head — not to spoon-feed meaning, but to invite the viewer to engage, to think, to meet the work in their own space of discovery.

Your exhibition In Praise of Beauty explores and questions notions of beauty through various mediums. How do you define beauty, and how does it manifest in your work? You mentioned that beauty can transform even the most powerful among us into the weakest in a moment—how does this concept influence the pieces featured in the exhibition?

If I may, I’m going to answer this question with a maxim/poem I wrote which says: “I said beautiful… not perfect.”

Adébayo Bolaji.

You’ve often exhibited internationally and participated in artist residencies in places like New York, including a residency with Yinka Shonibare MBE at Guest Projects. What draws you to these artist residencies, and what do you enjoy about being surrounded by other visions and creative contaminations, which is different from exhibiting as a solo artist? How does the bond with fellow artists shape your own work during these experiences?

A residency is a presence. Presence isn’t just about personal attention — it’s also about environment. And environment is information. The sounds, the smells, the architecture, the weather, the daily rhythm of a place — all of that is a form of intelligence that presses against you, reshaping one’s inner landscape. When I’ve been in residencies — whether in India, the south of France, or elsewhere — what I’ve felt is this deep nurturing of intelligence. It’s not just about making work; it’s about allowing your internal shape, your inner lines, to shift. Because difference creates pressure — and pressure creates new shapes, new ideas, new lines. That’s the beauty of residencies: they force you out of the comfort of your usual environment and into a living, shifting resonant field where your patterns can break open and reform. That difference is what feeds the work, often in ways you don’t even recognize until later.